- Home

- Sarah Lotz

Day Four Page 4

Day Four Read online

Page 4

She moved onto the last suite – V27 – the psychic’s cabin. Devil’s work, her mamita would have called it. Mrs del Ray was a grumpy old bitch to be sure, but she was generous – Althea had already made extra money by turning a blind eye to the bottles of alcohol in her stateroom. The second she inserted her master key-card into the lock, the door was yanked open and Maddie, Mrs del Ray’s skinny assistant, lunged at her. ‘Althea! I thought you were the doctor.’

‘You are sick?’

‘Not me – Celine. Mrs del Ray.’

Althea followed her into the bedroom, where Mrs del Ray was sitting in her wheelchair, staring slack-faced at the blank screen of the TV. The room smelled of alcohol.

‘Celine? Celine? Althea is here,’ Maddie said in a sing-song voice, as if she was addressing a child.

Mrs del Ray looked up, her head lolling back on her neck, her eyes unfocused. She giggled, and flapped a hand in a vague greeting.

‘What’s wrong with her?’ Althea asked, her eyes drifting to the empty bottle of J&B next to the television. The woman drank too much – Althea was the one who lugged her empties to the glass crusher – maybe that was why she was sick.

‘I don’t know. She’s acting confused. I called the fucking . . . sorry’ – Althea nodded primly – ‘I called for the doctor as soon as the ship stopped, but no one’s come yet.’

‘You have tried to call again?’

‘Yeah. Haven’t stopped. There’s no answer at all now.’

Althea unclipped her radio and buzzed her supervisor. ‘Maria? Come in, Maria.’ Static hissed back at her. She tried again, with the same result. Susmaryosep. ‘May I try your phone, Maddie?’

‘Go ahead.’

Althea picked up the receiver and dialled the medical centre, but it just rang and rang. Next she tried Housekeeping and Guest Services, but both pipped with a busy signal. ‘I will go to the medical centre in person and tell them to send the doctor.’

‘Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome,’ Althea said automatically. She didn’t mind Maddie – Celine’s assistant had always been courteous to her, without being patronising or over-friendly. And she was visibly worried. Perhaps there really was something wrong with the old woman.

Althea hurried out the stateroom, trying her radio again. Another gush of static. This was exactly what she didn’t need. She checked the corridor on the port side for Electra, who serviced the staterooms in that section – but there was no sign of her. It would be faster to use the passenger staircase to reach the medical bay on Deck Three, although housekeeping staff were forbidden in the area. She’d take her chances. Most of the crew would be at their muster stations, herding the guests, or dealing with the issues in the generator room, so she should get away with it. Down and down she ran. She held her breath and ducked her head when she reached the landing on Six, where two engineers were helping several grumbling passengers out of one of the stalled elevators.

As she jogged towards the medical bay door, she caught a whiff of smoke drifting through the serrated sheeting that covered the adjacent entrance to the I-95. She pressed the bell next to the door and waited. Nothing. She tried the handle, and when it gave, she stepped inside. The narrow waiting area, pharmacy and reception desk were empty, but raised voices sounded from behind a door at the far end of the waiting area. She moved over to it, stood on her toes and peered through the frosted glass window. The new doctor was placing an oxygen cup over the face of a hysterical crew member in a pair of filthy blue overalls. Next to him, a male nurse was ministering to a fellow in officer whites, who was also attached to an oxygen tank. But it was the man on the gurney closest to her who grabbed her attention. He lay absolutely still on his side, his arm outstretched. Sloughs of skin like obscene lace drooped off his forearm, revealing a section of yellow and red weeping tissue. As if he could sense her gaze he shifted his eyes and looked straight at her. She offered him a look of sympathy, but he didn’t react; his eyes were empty, as if he’d crawled inside himself to deal with the pain. She’d seen nasty burns before – she’d been visiting her mother in Binondo when a fire had ravaged a nearby factory – but the sight still made her stomach roll. The doctor hurried over to the burn victim and gently placed a hand on his forehead.

Shaking, Althea retreated back to the waiting area. The shouts from the room had become murmurs. The fire had to have been worse than she’d been told. And it was becoming rapidly warmer down here; the air-con was still out. Unsure what to do, she paced.

The last doctor, a Cuban man with bad teeth, had reportedly been fired for harassing one of the Romanian crew waitresses, but his replacement had a kind face. She wondered if she could ask him for help with her situation, then swallowed the thought. She couldn’t think like that. She ran a hand over her belly. If she was pregnant, it was still too early to show. Two months at the most. Perhaps Joshua had made good on his threat to mess with her pills after all. Bastardo. They’d fought the last time she’d been home, when she’d refused to cook for him and his brothers. How dare he expect her to wait on him after she’d broken her back on the ships supporting them all! It still made her insides burn with fury. He knew her greatest fear was turning into her sister, who was grey-skinned and washed out, living in squalor in Quezon with five children. What did he think would happen if she got pregnant? She would be fired, that was what, the money would dry up, and then all of them would be one step away from the slums. Him and his whole fuck-darned family. Well, guess what. That time will be coming sooner than you think.

It was her own fault. She should have married an American with money, not a stupid pinoy who’d been dumb enough to get himself fired off the ships. But no, she’d fallen in love – ha! Love! – with a fuck-darned assistant waiter with a mole under his eye who’d promised her they’d rise through the ranks together. She might not be able to divorce him – their families would never accept that – but she could leave. She could save up and start a new life.

It was a plan – a good plan – but if she was pregnant, she could forget it. She was only two months into her tenth-month contract, so there was no chance she could hide it.

‘What are you doing here?’ Althea turned to see a large woman with dyed orange hair and a crumpled nurse’s uniform bustling through the entrance door. ‘Are you sick?’

Althea explained about Mrs del Ray’s situation.

The woman gave her a tired smile. ‘Ah. Bin must have taken the call earlier, before we were overrun.’

‘The men who were injured in the fire,’ Althea said, gesturing at the door. ‘Will they be okay?’

The woman pursed her lips. ‘You went in there? That area is for patients only.’

‘So sorry,’ Althea murmured, automatically sliding into her deferential act. ‘No one was here. I was trying to find the doctor.’

‘Ah. Okay.’ The nurse ran a hand through her tangled hair. Dark circles ringed her eyes, and the skin on her nose and cheeks was florid with broken veins. A drinker. Althea knew the signs.

‘My supervisor said that the fire was not bad,’ Althea fished.

‘Things look worse than they are, don’t worry. I’d better get in there. Thanks for letting us know. V27, you say?’

Althea nodded, and dismissed, she ducked her way through the plastic sheeting and along the I-95. Trining’s station was on Five Aft – a five-minute walk at least. She jogged along the passageway, aware that the air was becoming muggier, the smell of smoke stronger the closer she came to the engine rooms aft of the ship. She swapped greetings with a group of waiters who hustled past her, their arms piled with trays of water bottles, but they couldn’t tell her more about the situation than she already knew. As she ran past the housekeeping offices, she heard the bark of Maria’s voice. ‘Althea!’

Althea froze, then turned to face her, eyes lowered.

‘I have been trying to contact you, Althea.’

‘I am sorry.’ She tapped her radio. ‘It isn’t working again.’

‘You have ch

ecked there is no one still in their cabin on your station? You have followed procedure?’

‘Yes, Maria. But one of my guests is sick and needs the doctor. They called down to the medical centre, but there was no answer.’

Maria glowered as if she considered Althea personally responsible for engineering the passenger’s ill health. One day, Althea promised herself, she would bring this puta to her knees. She would make her eat dirt and squirm. ‘I will see to it. Which stateroom?’

‘V27. It’s the fly-in – Mrs del Ray. I’ve already been to the medical centre and told them. May I go, please?’ Security must be checking that all the cards were in place by now, and Trining would blame her for the fact that her station hadn’t been checked.

‘Why didn’t you tell me that Trining was sick?’ Maria said in a dangerously soft voice.

Fuck-darned Trining. Althea was damned if she was going to cover for her this time. ‘I thought Trining would have told you immediately.’

‘She says you agreed to cover her station today.’

Althea put on her best innocent mask. ‘She did?’

Maria raised the twin pencil lines of her eyebrows. They never matched – one was always drawn on higher than the other, and they clashed with her white-blond hair. Learn to use a mirror, puta. ‘We are lucky there have been no complaints. She says she has not even begun the evening turn-down.’

‘I’m so sorry, Maria. There must have been some confusion.’

‘Paulo has checked that Trining’s staterooms are empty, but I need you to ensure he has been thorough.’

‘Will Security not do this?’

‘You are questioning me?’

‘No, Maria.’

‘After you have done that, you must go to your muster station and wait for further instructions.’

‘Yes, Maria. Thank you, Maria.’

How she hated to grovel, but she needed a good review if there was any chance of being promoted into a supervisor’s position. Not that there was much hope of that on this ship. The paisano system would come into effect – Maria would only give breaks to other Romanians. That was ship life. Sometimes it worked in your favour, sometimes it didn’t. And it didn’t matter that English was her first language. Her nationality counted against her. Someone had to do the dirty work. It had taken her over two years to work her way up from a staff steward (and the cones could be disgusting, but they were nothing compared to some of the officers) and secure the coveted station on the VIP deck.

She pushed through the service door that led to the lower decks, catching another whiff of the smoky odour. She hated this section of stairwell – there were thirteen steps up to each landing, and she counted them aloud to banish the curse. She knew it was ridiculous, but she couldn’t entirely shed her childhood superstitions – she still turned her plate whenever someone left the mess table.

As she opened the door onto Trining’s station, a blur of movement at the far end of the darkened corridor caught her eye. Someone was running towards her – a small figure. The light here was far worse than on her floor, but it looked like a child – a boy. How could that be? She’d been on cruises with spoilt American kids, running around like they owned the ship, the parents screaming at the staff every time one of the little snots got injured or lost, but the New Year’s cruises were for over-eighteens only. The emergency lights flickered, plunging her momentarily into darkness, before hissing on again. The child, fair-skinned, dark-haired and barefoot – was now twenty metres from where she was standing. ‘Hoy!’ she shouted, wincing as the lights snapped out again. She fought the urge to dive back into the service corridor. The lights blinked on – brighter this time – but the child . . . the child was gone.

She crossed herself automatically, jumping as a tall figure rounded the corner at the end of the corridor. She breathed easier as she made out the white shirt and black trousers of one of the security personnel. Had she imagined the child? Was her mind playing tricks? She was running on less than four hours sleep a night, so it was possible.

The guard stalked towards her. One of the Indian mafia, his face made up of hard angles. He towered over her.

‘Did you see a guest down here?’ she asked him, amazed at how calm she sounded.

He stared at her blankly. ‘No.’ He indicated the red cards slotted into the slots. ‘Have you finished?’

‘It’s not my station.’

‘Then why are you here?’ His hand strayed to the radio at his belt. ‘All crew must report to their muster stations now.’

‘I know. My supervisor asked me to check that everything was in order.’

‘And is it?’

‘I’m not sure.’ She didn’t want to tell him what she’d seen, in case it had been her imagination. But the child – if there even was a child – must have disappeared inside one of the neighbouring cabins, although she was certain she hadn’t heard the crump of a door opening and closing. ‘Do you mind if I recheck some of the staterooms? The steward who was sent to do it is new.’ Good. A lie, but it sounded reasonable. She waited for the guard to argue, but he merely continued to stare at her – perhaps he’d read something in her face – then waved a hand as if to say ‘go on’.

There were three staterooms that the boy could possibly have slipped inside when the lights went out. She opened the first, ducked into the bathroom, and then scanned the main area, opening the wardrobe to ensure that the child wasn’t hiding in there. There was no sign of him, but the room was a mess, the sheets scrambled into a ball, the bin overflowing with empty Coors cans. It was clear Trining hadn’t bothered to service her station at all that morning, and it was likely Paulo had just knocked on the cabin doors and then carded them without investigating properly. Trining must have God and all his angels on her side – it was a miracle no one had complained.

She glanced at the guard as she tried the next room, but he was fiddling with his radio. The second she opened the door, the acidic stench of vomit rolled out at her. She hesitated, then propped the door against its magnet and stepped inside. The bathroom was empty, and the rest of the space appeared to be unoccupied. She looked around for the source of the bad smell, aware that now she could also detect another odour: urine. It was faint, but unmistakable.

She crept around the edge of the dishevelled bed. The duvet was lumped between the wall and the side of the mattress, and poking out from the end of it, a pair of feet, the soles dirty and grey. She cried out and stepped back, bashing against the vanity unit and sending a make-up bag falling to the floor.

The guard was inside the room in seconds, scrunching up his nose. ‘What is it?’

‘Come here,’ she whispered. ‘Look.’

She watched the guard’s face carefully as he took in the scene. He recoiled, and fumbled for his radio. ‘Control, come in. Control.’ A hiss and a crackle. He banged it on his hand.

Althea couldn’t drag her eyes away from those feet. They belonged to a woman, and she found herself thinking about something her lola used to say when she was a child: that the shoes of the dead must be removed as soon as possible so that they are not weighted down on their journey to heaven. Barely aware she was doing so, she reached out to remove the duvet, but the guard placed a hand on her arm. His palm felt hot enough to burn her skin. ‘Wait.’ The guard climbed onto the bed, moved across it, and gently lifted the duvet covering the woman’s head, revealing a scribble of straw-coloured hair. He leaned down to check for a pulse, then replaced the coverlet exactly as it was.

‘Is she dead?’ Althea whispered.

‘Yes.’

They stood in silence for several seconds. The guard cleared his throat. ‘I must go outside to see if I can get a better signal. Do not touch anything.’ He softened his voice: ‘Will you be fine to stay here by yourself?’

She nodded.

‘Again, please do not touch anything.’ He hurried out, leaving her alone with the body. The hairs on the back of her neck danced. Althea closed her eyes, crossed herself ag

ain, and for the first time in many months, she prayed.

The Suicide Sisters

Helen reckoned there were some benefits to being among the few over-sixties on board; she and Elise had been allocated sun-loungers, while everyone else at their muster station had to make do with the floor. She was comfortable enough, but she could do without the racket. Next to where she and Elise were sitting, a group of men and women were flirting aggressively with one another, vying to be the centre of attention. The loudest of the bunch, a thirtyish man with the build of a rugby player and a pair of angels’ wings attached to his hairy back, was griping that the bar service had been suspended: ‘It’s why you go on a fucking cruise, innit?’ he droned on. ‘To have a drink and a laugh. And if the ship’s going to do a Titanic, then I wanna be as pissed up as possible.’ Nearby, an American couple, who resembled giant grumpy toads, were loudly complaining to whoever would listen that they would never sail Foveros again. She’d seen them once or twice in the dining room, ordering every entrée on the menu; they’d never once thanked their waiter.

And then there was Jaco, the ship’s one-man marimba/rock/reggae band (or whatever was required), who was wrapping up an off-key acoustic rendition of ‘By the Rivers of Babylon’. He’d arrived twenty minutes ago, presumably sent by Damien to distract them from ideas of mutiny while they waited to be dismissed from the muster station. He didn’t appear to be fazed that no one paid him the slightest bit of attention. In fact, being universally ignored appeared to be part of his job description as far as Helen could make out. She’d seen him all over the ship, hosting the Michael Jackson tribute evening, or lurking in the background during karaoke. She caught Elise’s eye and they both gave him a small round of applause. As if to punish them for their generosity, he launched into a clumsy version of ‘Jail House Rock’.

‘It’s a shame musicians are no longer required to go down with the ship,’ Helen said crisply, and Elise laughed.

The crew allocated to their muster station – a plump Australian woman with flinty eyes and a Filipino man with cheekbones like a supermodel’s – had long since given up telling passengers not to film the proceedings on their mobile phones, and were now chatting amongst themselves, occasionally offering bored platitudes to the passengers who harassed them for information. No doubt the people waving their iPhones around were hoping to sell the footage to one of the networks if the ship did indeed ‘do a Titanic’. Which was unlikely. If The Beautiful Dreamer was going to go down, Helen was sure it would have done so by now. She and Elise had been in the dining room deciding on their starters when the ship had shuddered to a stop and the lights died. There had been a few seconds of stunned silence, a single high-pitched scream, and then, in a clatter of dropped cutlery and raised voices, their fellow diners rushed – almost as one – for the exits. She and Elise had stayed seated and calmly finished their obscenely expensive champagne cocktails while the other passengers streamed past their table, rudely shoving the equally bewildered waiting staff out of their path. Few people appeared to heed the cruise director’s pleas to return to their cabins; most fled straight to the Lido deck where the lifeboats were situated. But now, a couple of hours since they’d all been instructed to head to their muster stations, that initial panic had turned into boredom and irritation.

Day Four

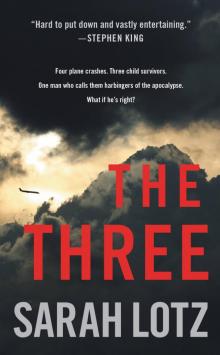

Day Four The Three: A Novel

The Three: A Novel The Three

The Three